Share

Draft withdrawal a step towards moratorium on biometric surveillance

As an organisation dedicated to digital rights and freedoms, fighting against the use of mass biometric surveillance, we welcome the decision of the Serbian Minister of Interior to withdraw the controversial Draft Law on Internal Affairs.

We call on the authorities to take another step and impose a moratorium on the use of advanced technologies for biometric surveillance and mass processing of citizens’ biometric data. Such a move would be in line with the recommendations of the United Nations and the European Union, as well as of numerous organisations and experts around the world.

We also call on the Ministry and the Government of Serbia to secure a broad public debate in the future law-making process, especially when intending to regulate the use of advanced technologies in our society, so that we could jointly contribute to the quality of laws concerning all Serbian citizens.

SHARE Foundation’s comments on the Draft Law on Internal Affairs

SHARE Foundation’s press release

Read more:

Total surveillance law proposed in Serbia

The public debate on the Draft Law on Internal Affairs has officially introduced into legal procedure provisions for the use of mass biometric surveillance in public spaces in Serbia, advanced technologies equipped with facial recognition software that enable capturing and processing of large amounts of sensitive personal data in real time.

If Serbia adopts the provisions on mass biometric surveillance, it will become the first European country conducting permanent indiscriminate surveillance of citizens in public spaces. Technologies that would thus be made available to the police are extremely intrusive to citizens’ privacy, with potentially drastic consequences for human rights and freedoms, and a profound impact on a democratic society. For that reason, the United Nations and the European Union have already taken a stand against the use of mass biometric surveillance by the police and other security services of the states.

SHARE Foundation has used the opportunity of the Draft Law public debate to submit its legal comments on the provisions regulating mass biometric surveillance in public spaces, demanding from the authorities to declare a moratorium on the use of such technologies and systems in Serbia without delay.

Although modestly publicized, only three weeks long public debate on the disputed Draft Law gathered national and international organizations in a common front against the harmful use of modern technologies. Among others, EDRi, the European network of NGOs, experts, advocates and academics advancing digital rights, reacted. The official letter to the Serbian government and the Ministries of interior and justice states that provisions of the Draft Law allowing the capture, processing and automated analysis of people’s biometric and other sensitive data in public spaces, are incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights which Serbia ratified in 2004.

“The Serbian government’s proposal for a new internal affairs law seeks to legalise biometric mass surveillance practices and thus enable intrusion into the private lives of Serbian citizens and residents on an unprecedented scale. Whilst human rights and data protection authorities across the EU and the world are calling to protect people from harmful uses of technology, Serbia is moving in a dangerously different direction”.

Diego Naranjo, EDRi

Gwendoline Delbos-Corfield, a French MEP from the Greens has warned against the use of these intrusive technologies and further restricting the rights of those living in Serbia, emphasizing that these technologies magnify the discrimination that marginalised groups already face in their everyday life. “We oppose this draft law that would allow law enforcement to use biometric mass surveillance in Serbia. It poses a huge threat to fundamental rights and the right to privacy”, said Delbos-Corfield.

“In Serbia, a country that Freedom House rated as only ‘partly free’, we suspect that the government has already begun the deployment of high-resolution Huawei cameras, equipped with facial recognition technology, in the city of Belgrade. If this draft law comes into effect, the government might have a legal basis for the use of biometric mass surveillance and the use of these cameras. Serbia now runs the risk of becoming the first European country to be covered by biometric mass surveillance. We call on the Serbian government to immediately withdraw the articles of this draft law that regulate biometric mass surveillance.”

Gwendoline Delbos-Corfield, MEP, Greens/EFA Group

The disputed provisions stipulate installation of a system of mass biometric surveillance throughout Serbia, without determining the necessity of the proposed measure for all residents of Serbia to be constantly treated as potential criminals by disproportionately invading the privacy of their lives. Of particular concern is the lack of a detailed assessment of the impact that the use of total biometric surveillance can have on vulnerable social groups, but also on journalists, civic activists and other actors in a democratic society.

SHARE Foundation comments on the Draft Law on Internal Affairs

Read more:

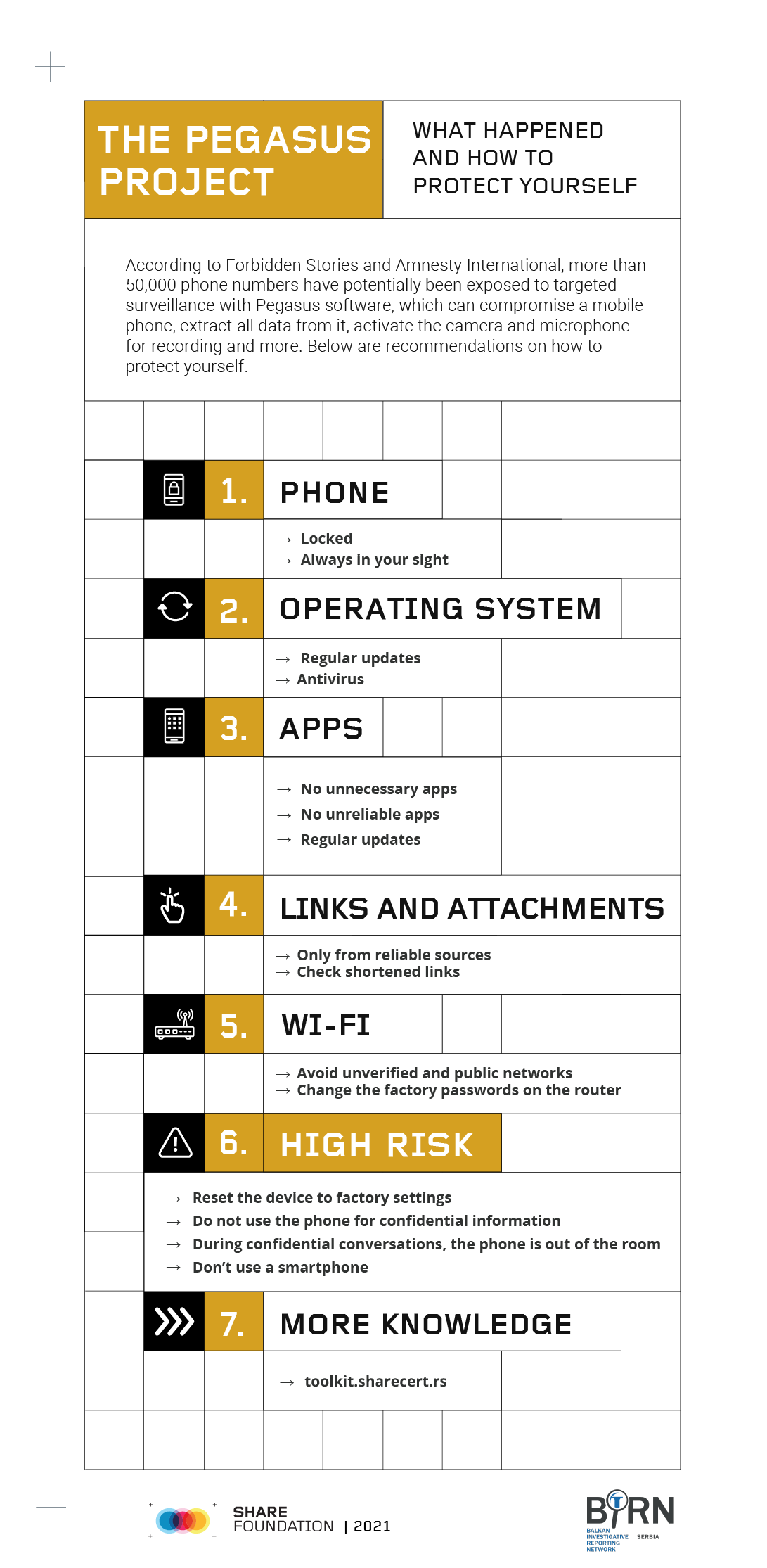

The Pegasus Project: what happened and how to protect yourself

More than 180 journalists were discovered in a database of phone numbers designated for potential espionage, thanks to a leak of documents given to the Forbidden Stories journalistic collective and Amnesty International. The choice of targets for surveillance was made by clients of the Israeli company NSO Group, which specialises in the production of spyware that it sells to governments around the world. Its primary product, Pegasus, can compromise a mobile phone, extract all data from it and activate the microphone to record conversations.

In addition to journalists, among the 50,000 people suspected of being targeted by state structures from around the world, there were activists, academics and even top public officials.

Targeted surveillance

Pegasus enables targeted compromitation of mobile phones, by hacking through malicious links or technical vulnerabilities in popular applications. In that way, it is possible to target a predetermined person and confidential information stored on their phone – correspondence with journalistic sources, business and state secrets, information on political plans and actions and the like.

Spyware

Spyware is a type of malware that collects data from an infected system and passes it on, usually to the person who created it. With such malware, passwords, personal data, correspondence, etc. can be collected without authorisation.

Pegasus

Use of software for iOS was discovered in 2016, but is believed to have been in use since 2013. Although NSO Group claims that Pegasus is intended to fight terrorism and international crime, human rights organisations have identified the use of software in authoritarian regimes against civic activists and dissidents, including the assassinated Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Who is using it

Among NSO Group customers are primarily state bodies authorised for conducting surveillance and interception of communications: intelligence and security agencies, police services and the military. Although information on 40 unnamed buyer countries is currently available, the Pegasus Project findings indicate that the spyware was used in Hungary, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Mexico, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Kazakhstan, Rwanda, India and the United Arab Emirates.

How it infects the device

The software is intended for devices running the Android operating system, as well as some iOS versions, and exploits several different flaws in the system. Infection vectors include link opening, photo apps, the Apple Music app and iMessage, while some require no interaction to run the software (zero-click).

What can it access

With Pegasus, attackers can reportedly gain access to virtually all data stored in the target’s smartphone, such as contents of SMS correspondence, emails and chat apps, photos, videos, address book, calendar data or GPS data. There are also options for remotely activating the phone’s microphone and camera and recording calls.

What can I do

Digital rights falter amid political and social unrest

SHARE Foundation and Balkan Investigative Reporting Network – BIRN, which have been monitoring the state of digital rights and freedoms in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Hungary, North Macedonia, Romania and Serbia since 2019, published a report on the violations of human rights and freedoms in the digital environment in the context of social and political unrest. From August 2019 to December 2020, the regional monitoring recorded more than 800 digital rights violations in an interactive online database.

Journalists, civil society activists, officials and the general public have faced vicious attacks – including verbal abuse, trolling, smear campaigns and pressure to retract content – in response to publishing information online. Many of our data were compromised and our privacy increasingly endangered with widespread surveillance, especially during the pandemic.

BIRN and SHARE took an interdisciplinary approach and looked at the problems from a legal, political, tech and societal aspect in order to show the complexity of cases in which the violations of digital rights and freedoms occur. Most online violations, a total of 375, were related to pressures because of online activities or speech, which includes threats, insults, unfounded accusations, hate speech, discrimination, etc. These issues create an atmosphere dominated by fear and hatred, which makes vulnerable communities such as LGBT+ or migrants subjected to additional attacks.

The main trends highlighted in the report are:

- Democratic elections being undermined

- Public service websites being hacked

- The provocation and exploitation of social unrest

- Spreading of conspiracy theories and pseudo-information

- Online hatred leaving vulnerable people more isolated

- Tech shortcuts failing to solve complex societal problems

Report findings show the need for legislative, political and social changes in monitored countries – the digital evolution must be viewed as a set of mechanisms and tools which primarily have to serve the needs of the people. The COVID-19 pandemic has proven that an open, free and affordable internet is absolutely essential in times of crisis. Only by insisting on accountability for digital rights breaches and providing education on the risks and possibilities of the digital environment can we hope to create a progressive, open and tolerant society.

Read more:

Digital rights faltering amid political, social unrest: What now?

The SEE Network of civil society organisations is inviting all interested participants to join the first online discussion and knowledge share on the state of digital rights in Southern and Eastern Europe on July 1.

At the July 1 event (3pm – 4.30pm, CET) BIRN and SHARE Foundation will discuss its annual digital rights report, together with other members of the newly established SEE Network; an online public event will be held at 3pm, where key trends concerning the digital ecosystem will be discussed.

In August 2019, BIRN and SHARE foundation started a unique monitoring process of the state of digital rights in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Hungary, North Macedonia, Romania and Serbia, collecting more than 1500 cases of digital rights violations in a public regional database.

In Southern and Eastern Europe, where online disinformation campaigns are endangering guaranteed individual freedoms, and while the decline in internet safety has become a worrying trend, citizens with poor media and digital illiteracy have been left without viable protection mechanisms.

The event will cover some of the most important trends mapped during the monitoring period, such as: the position and threats posed to the vulnerable groups, particularly focusing on gender perspectives; freedom of speech and online hatred; the effects of state propaganda and fake news on the right of citizens to receive accurate information; and (ir)responsibility of big tech companies in the region.

The event will gather representatives of CSOs, experts (both tech, legal and sociological), students, activists, tech enthusiasts and other interested parties in order to open a broad discussion on the growing challenges we face and the steps we need to take to counter the further deterioration of citizens’ digital rights, and press for policy change.

The event aims to provide space for diverse voices to be heard and we are delighted to invite you to join us by filling in this online registration form.

Upon registration you will receive a confirmation email and the agenda.

Digital security in one place

SHARE Foundation has developed the Cybersecurity Toolkit – an open platform that provides one-stop instructions and possible solutions to problems with websites, applications or devices, allows you to learn more about good practices in the protection of information systems and digital goods and offers advice if you are a victim of technology-based violence or harassment.

“Error 404” appears when you try to open your website, you can’t access your old email account because you don’t remember the password or you are considering which chat app is more secure than Viber? Tips on how to get through these and similar situations and much more are available in one place, making it easier to search when technology fails or your rights are compromised.

The tools are intended for citizens, journalists, activists, but also those with a little more technical knowledge to serve as a reminder. Our goal is to use our own resources and the help of our community to improve the knowledge base, tips and instructions over time so that the Toolkit is up-to-date with the changes in the digital environment.

Journalists, online media, activists and civil society organisations which are experiencing more complex technical problems can contact SHARE CERT at [email protected] (PGP Fingerprint: 3B89 7A55 8C36 2337 CBC2 C6E9 A268 31E2 0441 0C10). SHARE CERT, a special center for risk prevention in ICT systems, monitors and analyses security threats in the digital infrastructure of online and civic media in Serbia and provides them with pro bono technical and legal assistance.

Read more:

Clubhouse – our worst hangover yet!

Clubhouse is not the origin of all evil when it comes to compromising user privacy and the grave consequences of it. But, in the times we live in, where privacy became a household name and a recurrent legal and PR problem for established platforms like Facebook and Google; and with the presence of milestone regulations like the GDPR; one must wonder why would an emerging platform not only disregard all of the above, but also push the problem further in the wrong direction. Even from a business perspective, it does feel like Clubhouse did their market study based on data acquired from ten years ago. It only takes one look at the millions of users that WhatsApp lost this past January after an unfortunate change to their terms of service, to see that users have made a giant leap of awareness around data privacy. This also showed how readily available the alternatives are nowadays. Competitors who invest in privacy, like Signal and Telegram, were ready to welcome the mass migration which forced a giant platform like WhatsApp to backtrack.

Paul Davison one of the two founders of Clubhouse is behind the infamous Highlight app which among other issues was a nightmare for user privacy and safety. In 2020, an ex-employee of Highlight told Verge that Davison’s “entire perspective was always to push for, how do we get users to expose more data in the product?” and that “user trust and safety was completely an afterthought.” At least, we know that Davison is consistent.

Putting the marketing illusion of exclusivity aside and the fact that the last thing the world needs is another Social Media, Clubhouse stirs curiosity. As a sound enthusiast, I decided to join and check it out.

In order to be able to invite people across the door of exclusivity – assuming they own an iPhone – one has to grant Clubhouse access to the contact list. Upon doing so, Clubhouse recommends names to be invited, under which you can see how many contacts that person has who are already Clubhouse users. These are shadow profiles, data about users who didn’t submit it themselves but that we volunteer to Clubhouse (and its wide web of servers, governments and third party corporations). Joining Clubhouse and using its features is not only about one’s own data, but also the data of everyone on our phones. Shadow profiles in addition to users’ data, can be used to map social and political groups, networks, of racialized communities or individuals, or of people whose identities or beliefs are criminalized or which are of interest to authorities, corporations and adversaries: BIPoC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour), LGBTIQ people, activists, Human Rights Defenders… etc.

Clubhouse is a voice-based platform & our voices reveal a lot about our emotional and mental state. They can reveal our background, social class, and even personality traits. Our accents, our dialects, the expressions that we use, all tell our stories and the stories of the communities we belong to.

Clubhouse says that “the experience is more like a town square, where people with different backgrounds, religions, political affiliations, sexual orientations, genders, ethnicities, and ideas about the world come together to share their views, be heard and learn.” In the rooms I joined I noticed a certain sense of comfort among users. Which at a first glance is reassuring. Hearing familiar voices, especially in small groups, and especially at night, created an atmosphere of familiarity and intimacy. This led some users to share intimate details about their sexualities, personal stories and advice on migration and asylum seeking, and political debates around sensitive topics. I was terrified for this had to be properly relayed over secure encrypted servers, and within safety measures like knowing who is listening and if they can record what is happening. I dug in Clubhouse’s data use policy (aka privacy policy), and I checked what one can and cannot do on the app.

The platform, like many, is very ambiguous about how they store our data, and who they share it with and what for. Clubhouse uses servers based in the US which remains short on data protection especially with the extended reach of agencies like the NSA. The app also uses the Shanghai-based startup Agora for its real-time voice and video engagement. Being based in Shanghai and under Chinese jurisdiction, Agora is legally-bound to comply with the regulations of the Chinese government. Stanford Internet Observatory (SIO) revealed that Agora’s backend infrastructure receives packets containing “metadata about each user, including their unique Clubhouse ID number and the room ID they are joining. That metadata is sent over the internet in plaintext (not encrypted), meaning that any third-party with access to a user’s network traffic can access it. In this manner, an eavesdropper might learn whether two users are talking to each other, for instance, by detecting whether those users are joining the same channel.” This raises serious concerns about the privacy and safety of users discussing issues that the Chinese or the US government consider a threat.

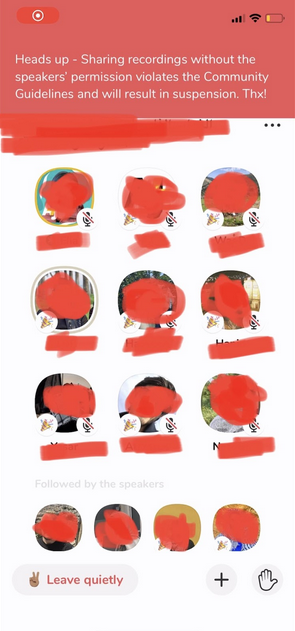

This past weekend (February 21st), a user managed to connect a Clubhouse API to his website, and broadcast the audio chats from various rooms in the app. Clubhouse confirmed the spillage to Bloomberg and stated that they suspended the user which violated the platform’s terms of service. Nevertheless, and using the simple screen grab feature of the iPhone (which Clubhouse so far is strictly built for), I managed to record whatever room I wanted to. Clubhouse did warn me that posting it without users’ consent can result in suspension. But how would they know what I could do with the recording? They can’t. Were the users informed that someone was recording their conversation? No (I asked some of them). Is it only about sharing the recording? Definitely not. An adversary be it a repressive regime, an intelligence agency or a hate group can employ the recording for a myriad of threats.

Screenshot of the video recording from a Clubhouse room. The recording was deleted after testing.

Clubhouse started with an alerting disregard to user safety which journalist Taylor Lorenz documented through her own experience on the platform. This was followed by various reports about the platform being used to spread racism, antisemitism, misogyny, and a barrage of conspiracy theories.

It all boils down to Clubhouse’s lack of understanding, premeditated or not, informed or not, about the risks of running such a space with such an infrastructure and such basic mistakes.

Who starts a social media platform in 2020 without a block or mute button (though this important feature was added later on). The platform makes commendable statements against abuse in their terms of service, yet it still falls short on the mechanism to address user safety and the process for accountability when there is abuse. Though they claim to address “incident” reports of abuse swiftly, the process raises serious questions. Upon an “incident” report, the platform will keep a “temporary audio recording” which is retained “for the purposes of investigating the incident, and then delete it when the investigation is complete.” Sounds good on paper, but what happens when a for-profit platform, that has major issues with data privacy, transparency, and an alarming infrastructure; is the investigator, the judge and the enforcer of the sentence? And on top of it, they will delete the evidence when they themselves deem the issue settled. Of course, this is not a call to record and document what is being said on the platform. This is to inform the users, and to highlight Clubhouse’s lack of the vision and knowledge that are crucially needed to address such complicated and dangerous issues. Problems other platforms with much longer experience and a wide array of scandals have been struggling with for years.

Finally, the platform doesn’t provide an easy and accessible option for users to quit. It is closer to entrapment. I wish I was told before I joined that there is no “delete account” button, let alone an easy way. Rather, users are thrown into a Kafkaesque process where it is not clear when I can be freed, how long that will take, for how long they will keep my data, and meanwhile where it will be stored and what for.

For now, I am stuck. Meanwhile, I will keep silent in the Club. I will not give Clubhouse any access to anything I can control on my phone. From inside the Club I can tell you, if you are still standing outside, think twice before coming in. It is a nightmare as it is, but it has the potential of spiraling into a much worse nightmare.

Leil Zahra is a transfeminist queer filmmaker, researcher and trainer on digital security and data privacy, born in Beirut and based in Berlin. Their work has a major focus on migration, anti-racism, decolonialism, queer politics, and social justice.

Read more:

The 2020 RDR Index: Digital Giants and Human Rights

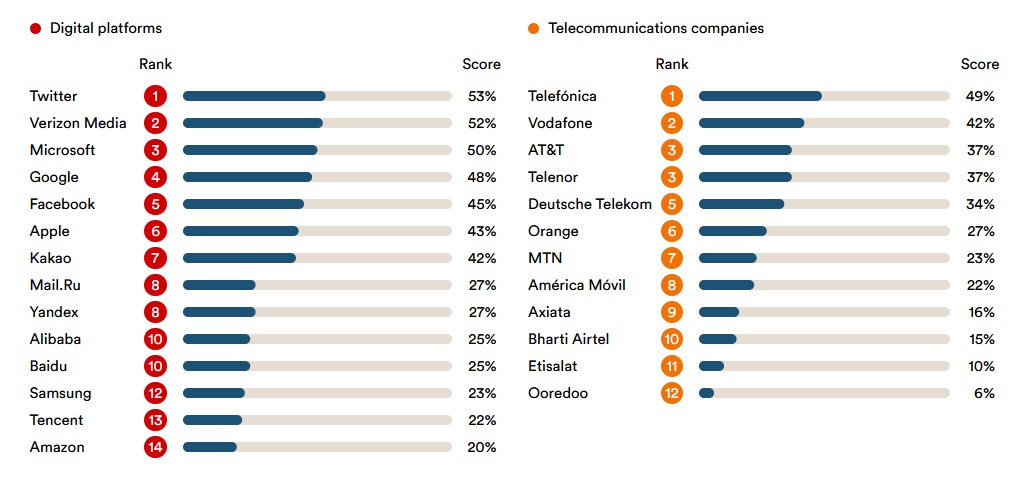

Despite notable improvements by a majority of most powerful digital platforms in their publicly disclosed commitments and policies affecting privacy and freedom of expression and information, the global internet is still facing a systemic crisis of transparency and accountability, concludes the new report of the organization “Ranking Digital Rights” on Corporate Accountability Index for digital rights in 2020.

Published on Wednesday, February 24, the RDR Index evaluates the work and policies of the 26 largest digital platforms and telecommunications companies that held a combined market capitalization of more than $11 trillion. Their products and services affect a majority of the world’s 4.6 billion internet users.

Digital platforms and telecommunications services users “lack basic information about who controls their ability to connect, speak online, or access information, and what information is promoted and prioritized”, the statement added.

“The most striking takeaway is just how little companies across the board are willing to publicly disclose about how they shape and moderate digital content, enforce their rules, collect and use our data, and build and deploy the underlying algorithms that shape our world,” said Amy Brouillette, research director for Ranking Digital Rights.

The fifth RDR Index has two new companies added, Amazon and Alibaba, while the methodology was expanded with new indicators that examine company disclosures related to their use of algorithms and targeted advertising. Among other experts from around the world, Olivia Solis Villaverde and Bojan Perkov from the SHARE Foundation participated in the preparation of this year’s report.

Results of the 2020 Index

The 2020 RDR Index shows Twitter taking the first place among digital platforms due to its comparatively strong transparency about its enforcement of content rules and of government censorship demands. For its strong human rights commitments, the Spanish Telefónica retained its top spot among all rated companies, including digital platforms.

Of all the evaluated companies, Qatari’s telco Ooredoo ranked lowest as it disclosed less than any other telecommunications company about its governance processes to ensure respect for human rights. The e-commerce giant Amazon ranked last among digital platforms, due to low ratings of transparency and accountability around users’ rights, and for disclosing very little about how it handles or secures user information, and nothing about its data retention policies, despite its deep reliance on user data to fuel its business model.

Since the launch of the RDR Index in 2015, the number of companies that are actively improving the protection of consumer rights and freedoms has been growing, while compared to previous year there has been an improvement among all evaluated companies – except Google and AT&T. Such progress is noticeable even among the lowest rated companies headquartered in restrictive jurisdictions, such as Russia, South Africa, China and the Middle East.

A detailed report is freely available at Ranking Digital Rights.

Read more:

Request to ban biometric surveillance enters European Parliament procedure

As of February 17, citizens of the European Union have been signing a petition for a ban on mass biometric surveillance in order to force the European Parliament, with one million signatures, to include this request in its agenda. At a time when the EU is preparing laws on artificial intelligence, dozens of civil society organizations, numerous activists and experts have called on the citizens of member states to use the unique opportunity to incorporate the protection of freedom and dignity into regulations that will shape the future.

Public pressure on the Union’s legislators is part of the joint, pan-European campaign #ReclaimYourFace which was launched last fall, and in which Serbia also participates through the SHARE Foundation and the local initiative #hiljadekamera, #thousandsofcameras. A campaign to ban mass biometric surveillance in public spaces in European cities has been launched in coalition with the European Digital Rights Network (EDRi) and several European and global organizations.

The petition launched by SHARE at the time, although with no formal influence on national lawmakers, gathered close to 15,000 signatures in just a few weeks.

The citizens of Serbia are particularly interested in the urgent suspension of the mass biometric surveillance project, which is already being implemented in Belgrade, in conflict with the Constitution and laws. With thousands of smart cameras on the streets and squares, our capital city will become the first city in Europe to impose life under constant surveillance on its citizens and visitors.

EU citizens’ signatures for a petition to the European Parliament are being verified. If you are a national of one of the Member States, please sign.

Read more: